If your dog was to be subjected to an aversive, would you rather it occurred randomly or control the timing yourself?

I put this question to a rational positive-reinforcement trainer, who responded unhesitatingly that she would prefer to control the timing of the aversive, so as to minimize fallout, and in order to potentially create some practical inhibition.

The logic of her choice hinges on a pair of sensible assumptions. First, that controlling an aversive (even just the timing) naturally lends any competent handler the opportunity to avoid (or at least temper) detrimental associations; second, that the well-timed application of an aversive has potential utility. Of course, she would prefer to avoid aversives altogether, and clearly stated so.

No surprise, given the well-publicized risks. According to the American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior,

the potential adverse effects of punishment [include] but are not limited to: inhibition of learning, increased fear-related and aggressive behaviors, and injury to animals and people[1]

Moreover, we are warned that risks such as extreme generalized fear and negative associations with the dog’s environment or handler, can occur “regardless of the strength of the punishment.”

This last claim must rest on belief in a dark sort of behavioral homeopathy, whereby the magical effects of punishment [2] endure despite its infinite dilution.

But there is another problem. If we accept that the experience of even mild punishment carries an arguably prohibitive level of risk, and we acknowledge that the deliberate application of an aversive is nonetheless safer in obvious respects than allowing exposure to randomly occurring ones, how is it that trainers come to fret over distilling off every atom of punishment from their training programs, while blithely acknowledging that naturally occurring aversives are both largely unavoidable and relatively innocuous?

One would think such events as getting stepped on or startled would carry a risk (of potentially extreme and irreversible fallout) equal to that borne by the deliberate application of a comparable aversive. Yet few cautionary tales exist to illustrate these hazards, such as happen to dogs every day of their

lives, often right in the presence of their owners or at their owners’ very hands.

lives, often right in the presence of their owners or at their owners’ very hands.

Even the authors of some of the most dire warnings regarding the purposeful use of aversives to punish behavior, seem to understand that the bulk of natural or accidentally inflicted aversives are fairly harmless.

I imagine it is intuitively obvious to them, as it is to me and to the dog-owning public, that a dog’s stubbing its toe while chasing a frisbee is unlikely to sour him on the game or ruin his relationship with the person who threw it.

So, what makes the demon punishment so extra-special potent, and its measured application so inescapably treacherous, compared to those unplanned aversives our dogs regularly suffer and gracefully overcome?

Aversives v. Punishment

Karen Pryor explains the critical distinction in a 2007 blog post (emphasis mine):

There’s a difference between aversive events and punishment. Life is full of aversive events—it rains, you stub your toe, the train leaves without you. These things happen to all of us, and to our pets, and we don’t control when or if they occur. Kay Laurence has an amusing paragraph about the aversive events that befall her Gordon setters (all of which they ignore)—falling off the bed, running into door posts, and more (read that article here).

In general, all that we learn from the inevitable aversives in daily life is to avoid them if we can.

On the other hand, a punishment is something aversive that you do on purpose. It may be contingent on a behavior, and it may stop or interrupt that behavior—which reinforces YOU for punishing, so watch out for that.

I find this explanation notable for several reasons.

First, it happens to be framed in response (albeit indirect) to the question, “Can you teach everything without punishment?”, yet that question is in no way addressed either by the above or within the remainder of Pryor’s comments.

It does, however, illustrate the tendency to frame discussions on tools and methods in terms of human intent, rather than in terms of the dog’s actual experience.

It’s a common tendency–and problematic, as when assumptions regarding the intention behind either the design or application of a given tool are offered as proxy for an objective analysis of how the tool actually operates or is actually applied.

Consider the myth, held true by many and even promoted by such authorities as Dr. Karen Overall, that head-halters are non-aversive. It’s an error that persists despite the reality that dogs do not casually accept wearing them, nor reliably tolerate being steered or restrained with their assistance.

It’s surprising that a phenomenon so widely observed and even scientifically documented [3] would be so widely ignored. But if we accept that our intentions are directly relevant to any and all contemplations of tools and methods, it’s only a small leap to imagine they may represent an acceptable standard of measurement.

And if we buy that, head-halters clearly rate as non-aversive by virtue of their gentle intention (indicated right there on the package), whereas prong and electronic collars may fairly be judged inhumane by virtue of being, as Dr. Overall put it in a 2007 editorial, “rooted in an adversarial, confrontational interaction with the dog.”[4]

Why would anyone invest in a scheme so clearly divorced from objective analysis?

For starters, it allows one to rationalize bypassing the complicated business of assessing how a given dog experiences a given tool wielded by a given trainer under given circumstances, instead suggesting a far easier equation, according to which one need only infer a tool’s intention in order to gauge its virtue.

This represents a boon, of course, for the purveyors of tools designed more for the purpose of persuading us of their kindness than actually facilitating it, as well as for anyone in the business of evoking faith in good intentions above promoting trust in skill or effectiveness. Moreover, substituting cursory judgements for true investigation is a real time-saver, freeing one up to concentrate one’s efforts on cementing the stigma attached to those intentions deemed impure, or on promoting the prohibition of those tools and methods associated with them.

But most importantly, it diverts attention from the fact that to a dog, an aversive is just an aversive, whether willfully administered or the result of mere clumsiness, a point that–if fully appreciated–would stand to undermine the endowment of punishment with extra-normal danger and potency.

To be clear, I’m not arguing for or against specific equipment or methods. I’m suggesting good intentions wield little to no dependable influence over how much a dog gains or suffers. And until we make a practice as an industry of evaluating the effect of our actions independently from the righteousness of our intentions, we may remain blind to those cases where to two are in conflict.

“I Can’t…”

Suzanne Clothier lately posted some thoughts on punishment under the title “I had to…”. On her blog, she takes positive trainers to task for dodging responsibility in instances where they’ve made the choice to punish. She offers examples of what she evidently considers lame excuses, like “the client was frustrated,” or “I had tried everything else.” And she challenges trainers to do better:

Replacing the phrase “I had to. . .” with “I chose to. . .” puts the responsibility where it belongs: on the trainer who made the choice to use techniques or equipment. It helps us all remember that in making that choice, by definition we excluded other possibilities. When using force, we need to be very clear that in discarding other options, other possible solutions, we may also be choosing to limit what is possible when we push ourselves.

For the record, I agree force is often used too casually, without due consideration of alternate strategies, and that acting out of mere convenience or fustration should be roundly discouraged. I also believe in the importance of accountability in dog training across the board. However, I was struck reading Clothier’s article by what seemed a misplaced focus on the moral peril (for lack of a better term) associated with use of force, rather than on any harm–real or presumed–that might be dealt the dog as a result.

She details an event involving a young Labrador who’d just head-butted her very hard for the second time, and describes the moment in which she considered her options:

I began to think, “One good correction might get through this dog’s thick skull.” I surprised myself by thinking that, but then I further shocked myself (and some of the audience) when I asked the handler explicity for permission to use a physical correction on her dog. She agreed, trusting me as a trainer to do right by her dog.

In that moment when she trustingly agreed to let me use force on her dog, I found something in myself that surprised me further: a little voice that challenged me to push myself further, to help this dog without force. It was like having a gauntlet thrown down at my feet. Do it without force, without ego, without justifying force.

Compelling words. But what does Clothier’s internal struggle have to do with the needs of this somewhat thick-headed young dog?

We are meant to assume he benefited from Clothier’s suppression of her ego, to understand that what he needed most in that pivotal moment, was not “one good correction,” but rather for Clothier to “take up the gauntlet” and turn the other cheek.

But it’s impossible to deduce that from Clothier’s narrative, because it has nothing to do with the dog’s experience.

Instead, she gives us a parable about overcoming temptation and perfecting one’s intention. Good stuff from a personal improvement standpoint, but no substitute for a reasoned consideration of whether a correction might have been productive. Granted, not the point. But what is??

That we are accountable for our choices to use force, yes. That one should not act out of ego or vengeance, clearly. But was that the temptation Clothier resisted? Remember, she didn’t just refrain from lashing out in anger. She suppressed the instinct to consider punishment as an option.

Despite Clothier’s drawing the familiar analogy between the application of a training correction and the specter of wife-beating, this is ultimately not a lesson in tempering one’s anger or shoring up one’s patience. It is a lesson in training one’s inner voice to distrust one’s rational mind.

Clothier equates the use of aversives with the use of force, and equates force with violence. She frames its contemplation as a sign of moral weakness, and the decision to use “force” as a failure by definition:

Whatever the answer, the solution is to recognize where I went wrong.

Dog training is many things, including a lesson in kindness and patience. But it should not be exploited as a proving ground for fringe notions of moral perfection.

If “I had to…” is a cop-out, then so is “I can’t…” After all, in making that choice, aren’t we also “choosing to limit what is possible”?

Bible and Hatchet

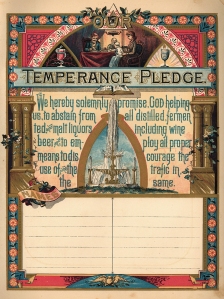

Meanwhile, a generation of trainers is being bullied into signing blood oaths constraining them from ever practicing the productive application of aversives.

Jean Donaldson, Karen Pryor, and Victoria Stillwell all require pledges from their disciples, while selling the public on the idea that hobbling oneself with a vow of irrational temperance is a mark of enlightenment.

The result is a murky and oppressive climate, often dominated by vitriol and intolerance, as in Dr. Karen Overall’s unsubtle insinuation that owning a choke, prong, or electronic collar may lead to child and spousal abuse:

Without exception, such devices will make my anxious patients worse and allow the anger level of my clients to reach levels that are not helpful and may be dangerous. The link between dog abuse and spousal/child abuse is now well-established (Ascione and Arkow, 1999; Lockwood and Ascione, 1998).[4]

Like Pryor’s warning to beware the utility of punishment, lest one’s urge to punish be strengthened, Overall here concerns herself with the threat punishment poses to us. It’s a clumsy argument at best, and less than cleanly scientific. But it succeeds in promoting the point that punishment is poisonous and intoxicating, while skirting the question of what that has to do with training a dog.

Child abuse is real. Animal abuse is real. Drunkenness is real. It’s a fact there are cretins and criminals within our ranks.

Likewise, there’s a history of countering such abuses with fear-mongering, misinformation, and hyperbole. And science, or some fractured fairy tale version of it, has been drafted into these campaigns before.

These tactics are effective, which I’ve heard is reinforcing. But they are a rejection of reason, and an abuse of the influence their authors wield. It’s as old school as tent revivals and temperance unions, and as backward as beating a dog.

There are solid arguments for taking care in applying aversives. But there is no credible foundation, scientific or ethical, for the wholesale exclusion of aversives from a training program, except if one accepts the idea that the very willingness to punish is perverse, and so fit to be stigmatized and suppressed.

Take away that belief, and the dragon vanishes. One is left with a serviceable tool and a solvable problem. The dog doesn’t know you are putting your soul at risk. He doesn’t even need to know you did it on purpose.

It’s not rocket science. It’s not alchemy.

It’s just good bar tending.

—————————–

1. AVSAB Position Statement: The Use of Punishment for Behavior Modification in Animals. 2007.

2. I use the term “punishment” here and throughout this post in the same arguably vague way as the sources I’m quoting, to denote the deliberate application of an aversive to discourage behavior.

3. L. I. Haug, B. V. Beavera and M. T. Longneckerb, Comparison of dogs’ reactions to four different head collars, Applied Animal Behaviour Science Volume 79, Issue 1, 20 September 2002, Pages 53-61

4. Overall, K.L., 2007. Considerations for shock and ‘training’ collars: Concerns from and for the working dog community. Journal of Veterinary Behavior: Clinical Applications and Research. Res.2, page 106.

© Ruth Crisler and Spot Check, 2012.

100 comments

Comments feed for this article

January 20, 2012 at 5:03 pm

Linda Kaim

Will go down in the annals of my all-time favorite posts ever written. Absolutely spectacular!

January 20, 2012 at 5:09 pm

Eric Lundquist

Why didn’t I know about this blog sooner.

Just became my favorite.

Great writing Ruth!

I bow to your ability.

Eric

January 20, 2012 at 10:32 pm

ruthcrisler

Welcome, Eric. Make yourself at home.

January 20, 2012 at 5:18 pm

Miz Pierson

Brilliant. Simply brilliant. Thank you.

January 20, 2012 at 5:33 pm

cathie

Once again Ruth… spot on!!!

January 20, 2012 at 6:06 pm

Rob McMillin

Jean Donaldson, Karen Pryor, and Victoria Stillwell all require pledges from their disciples, while selling the public on the idea that hobbling oneself with a vow of irrational temperance is a mark of enlightenment.

It’s interesting that this comes up in the context of temperance, because I could have sworn I read a very similar story in the context of sex at the Guardian earlier in the day. In other words: it’s all social, and contextual.

January 20, 2012 at 10:21 pm

ruthcrisler

Fascinating article. Thanks for the link!

January 20, 2012 at 8:21 pm

Cynthia Eliason

They believe that naturally-occurring aversives are harmless. And this from Pryor: “In general, all that we learn from the inevitable aversives in daily life is to avoid them if we can.” If they recognize this, why then are they so opposed to Koehler’s method of introducing training using a longe line and choke collar? The handler in Koehler’s books is part of nature. He naturally and consistently responds in a predictable way to natural events. When there is a Northbound dog in front of him on the longe, his naturally-occurring behavior is to move briskly and purposefully Southward. The result is a naturally-occurring aversive. The dog takes no offense at it, but learns to avoid it if he can.

It almost sounds as if they want to deny the trainer his place in nature, as if they won’t allow him to be a creature with certain naturally-occurring behaviors, such as walking or jogging in a direction of his choosing at a time of his choosing. It almost sounds as if they think the trainer is just doing it to be unkind to the dog! Isn’t that strange?

January 24, 2012 at 10:54 pm

ruthcrisler

Interesting observation.

January 20, 2012 at 9:41 pm

FoxStudio

I refuse to believe that it is wrong to tell my dog “no”, in language (sometimes physical, but never anything that would cause him pain) that he can understand. It’s not about me. It’s about being clear to him what I want and what I don’t want. That only seems fair.

It seems like there is some weird thing going on with these women, and they are all women, aren’t they? I guess I can say that because I’m a woman, too.

Great post! Glad I’ve found your blog.

January 20, 2012 at 11:42 pm

ruthcrisler

Yeah, sorry to say the save-your-soul-through-positive-reinforcement trend is clearly driven by women.

January 20, 2012 at 9:55 pm

Jonathan Klein

Really Well Said! Thanks

January 20, 2012 at 9:57 pm

A thought on training approaches! - German Shepherd Dog Forums

[…] greatly in the last 30 years. I believe in good training…. You might like this blog post: Undue Temperance Spot Check __________________ Christine Blackthorn Working German […]

January 21, 2012 at 5:43 am

pawsforpraise

Sorry, not buying it. Certainly dogs encounter similar naturally occurring aversives in nature as humans do. Fine. But, too often, humans use aversives against dogs in a way that borders on abuse, and I would much rather sign a pledge not to use them than sign one that prevents me from speaking out against the ones that I, and likely most dogs, find the most painful or annoying. The hidden damage from your post is that you will undoubtedly now become the darling of the choke, pinch and shock crowd, where aversive tools are their FIRST choice, not their last, and have nothing to do with what a dog would encounter in nature. Positive trainers do have an obligation to see that the tools they use are the least aversive to the dog, but saying that a head halter is aversive does not make a shock collar benign. Also, the use of the term “disciple” is interesting. I am no one’s disciple despite the fact that I may share opinions with some of the people you mentioned. If you really want to experience the concept of disciples, I suggest you visit any Cesar Millan page, or any shock collar trainer’s pages on youtube or facebook. You will not find positive trainers there, not because they don’t want to engage in rational discussions of what really makes dogs tick or of controversial topics, but because those people tend to ban those they don’t agree with from their sites. What are they so afraid of? Your article is, at least, fairly well thought out as a debate position. But, if the fallout is that you encourage another member of the public to treat a dog harshly (and how many of them are doing it with any sense of the science or the possible fallout) then, in my opinion, you should just have left well enough alone.

January 21, 2012 at 7:45 am

ruthcrisler

The choice between swearing total abstinence and endorsing abuse is a classic false dilemma.

Beyond that, your comments all go to why I shouldn’t make my argument, not to why it is in the least invalid.

Critical thinking and honest debate are not nearly as dangerous as their suppression, I think. Leaving well enough alone doesn’t get us anywhere.

By the way, you might enjoy my post on Cesar Millan.

January 21, 2012 at 4:26 pm

regina steiner

I find myself looking for the “like” button 🙂 Ruth I appreciate what you’ve written here! I consider myself a trainer who uses a lot of positive reinforcement in training, especially in the teaching phase, but fully believe that aversives have their place in training. I have no patience with trainers who go so far out of their way to avoid an aversive that the dog ends up on the losing end of the deal.

January 21, 2012 at 8:26 am

Rise VanFleet, PhD, CDBC

While you make some good points, and you’ve clearly thought a lot about this, I am concerned that some of the quotes you use for your arguments are taken out of context (either of the article/book itself or of that author’s well-known body of work). I think that we need to make a distinction between human rationality, emotion, and where intent fits in there. The internal reactions that we have in stressful situations are often emotional, and do not always follow reason. Human emotional reactions are influenced by many things not “of the moment” and can clearly be out of proportion at times. And humans express their intent through their body language, tone of voice, and facial expressions. We know that dogs read this exquisitely well, so I would not be quite so quick to dismiss intention as part of the bigger equation. I agree it needs to be teased apart from methodology, but ultimately, intention matters to the dog and our relationship with the dog. Just about all professions involved in changing others (for example, psychology) have an ethical code that guides the use of methods. I’ve just taken a course on the use of human subjects for a research project I am taking part in (mandatory from the university with which I’m collaborating, course is from the NIH). As a practitioner, I must follow various ethical codes or risk losing my license, and I’ve witnessed the damage that has given rise to such ethical codes to guide decision-making and behavior. I think that ethics are exceptionally important to apply, whether any method is effective or not. I think it’s a good thing that when we are considering the use of any method with our dogs, children, horses–anyone under our care–it’s a very good thing to take the time to sort out our own emotions, intentions, and to apply rational thought, but also to think about the ethical considerations. I have found it very useful in my work with canines to apply what I have learned –methods, intentions, ethics– in working for decades with children and families. Not only is there room for such considerations, I think we should be applying them at every turn.

January 21, 2012 at 9:13 am

ruthcrisler

Rise, thank you for commenting.

To your points, the quotes I pulled were intended to represent a particular brand of argument, and do so accurately, I think. They were not meant to represent anyone’s whole body of work. I agree, of course, regarding dogs’ ability to read what humans telegraph, whether knowingly or not, on a more emotional level via a complex array of subtle cues. But that is different from their experiencing, in any meaningful sense, at least, our intention. And a good trainer may reveal or hide his intention at will. As you put it, the question of intention should be teased apart from methodology.

Ethics are again a separate question, and one I agree is very important. But good intentions do not reliably generate ethical behavior. So, I see the “teasing apart” of these questions as critical to developing a respectable body of ethical thought in dog training.

By the way, I think a lot about other things, too .

January 21, 2012 at 11:42 am

Ada Simms

Thank you Rise for your comment. If I passed this article on to my students of family pet owners, they would be at least, a little confused. They would ask me a ton of questions “critical thinking?” or “so what is she saying about using aversives?”

Ethics IS a part of dog training as well as any field that deals with humans or animals. Being a Certified Police Ethics Instructor and how it definitely affected how police officers carried out their duties, it also has great importance on how a dog training humanely carries out their responsibilities.

When you belong, willingly, to a group that has a Code of Ethics, you do so by choice. Followers of Karen Pryor, Victoria Stilwell, Jean Donaldson and the like, agree to promoting humane treatment of animals.

Your comments about them as if they made us drink some “special” coolaid is quite offensive.

But then again, reading the comments following your article, most of us dog trainers are women and not capable of critical thinking.

January 21, 2012 at 12:15 pm

ruthcrisler

My use of the word “disciple” was tongue-in-cheek, unlike Clothier and Overall’s comparisons between training with aversives and wife beating.

By the way, I am a woman myself, as are majority of the readers of this blog, I’m guessing. What’s your point?

January 21, 2012 at 2:21 pm

Ada Simms

My point was based on your point.

“Yeah, sorry to say the save-your-soul-through-positive-reinforcement trend is clearly driven by women”

“Sorry to say!!!” What was the point of making that statement? The positive reinforcement trend was started by a man, Dr. Ian Dunbar. There are many great Vets, Trainers, Scientists… also men who share the same view to do resort to force and call it training.

It is quite clear Ruth from your writings, that animals are less valued than humans. Therefore, do what works..for YOU.

When intelligence ends, the conflict management tool box is empty, solution solving is exhausted, let’s resort to force to get the job done… just like the majority of men that govern countries.

January 21, 2012 at 8:50 am

cheshirecat2264

Thank you!! Logical use of tools to improve and enhance our partnerships with our canines should always be priority while working with our canines to teach life skills and build living partnerships.

January 21, 2012 at 10:02 am

julia Priest

Brilliant. So many of today’s “trainers” are more concerned with their agenda than with solving problems. Is it possible to use positive reinforcement to solve a lot of problems in dogs? Of course. Is it practical? Not always. Does the dog really care as much as these people purport? I doubt it. My main studies of dogs occur in observing the many that I raise and live with and I see that dogs are amazingly resilient and seem to have no long term damage when corrected by each other, or for that matter, me. “One good correction” works miracles when its is a GOOD correction– that is, it makes sense to the dog is well timed and intentional, and not delivered in anger.

You took the time to write so clearly what we all know is true, and as for he doubters, go ahead. Do it your way, I don’t care. But I know for an actual fact that my clients cannot and will not wait for the “magic” of +R when they have a 3 year old 90# Lab knocking down their kids and dragging them down the street. I have done lots of follow up, and while I have not administered any scientific tests or conducted in depth interviews with the dog, I see the dog looks happy and behaves itself and gets to stay in its home instead of rotting in the pound waiting for the magic of well timed cookies to take hold.

January 21, 2012 at 10:20 am

Nitesh Shah

I don’t think the +R trainers are even going to read this, of course never seen nor heard +R people spaek about their mistakes too. Thanks to their Genetics & its Behavior.

John R.

January 21, 2012 at 12:50 pm

Sarah

Great post. And what you hit on towards the end, equating actual ABUSE with a correction/aversive in a training context, is so widespread and misapplied it’s amazing that it’s allowed to go on. But it has become par for the course for many trainers that must endure these unjust accusations from dog fanciers that have taken it upon themselves to claim “morality” for themselves. I have a book that I have yet to read, it was recommended by another trainer and you might want to pick up a copy, called “Just a Dog; Understanding Animal Cruelty and Ourselves” by Arnold Arluke.

Training a dog using a correction is so far removed from ACTUAL animal abuse, that for a trainer or anyone else to equate the two is to diminish the plight of dogs that actually ARE victims of cruelty and abuse. To hear a recreational dog trainer or dog enthusiast say that it’s “cruel” to place an e-collar around a dog’s neck is to not really understand or respect what animal cruelty is and it belies a level of disassociation from reality that is truly startling, especially if the individual purports to be a training authority.

There’s a reason trainers that incorporate “aversive” handling methods and tools are in business. It’s because if people want to save their immortal souls, they’ll go to church, not call in a dog trainer for a lecture. If they have a serious, nagging, annoying, or egregious dog behavior problem to solve they will call a dog trainer that can get the job done. And while I am by no means the perfect trainer and still have much to learn (and am actively seeking to learn it), almost every one of my clients has done some form of “all positive” training before working with me.

They guiltily tell me that they are a bad person for wanting to “correct” their dog but that they have been doing all positive training for months with no improvement. Or that their dog is great in the classroom but not at home. And when they asked their instructor what to do, they were told to use better treats, wait, be more patient, manage the environment indefinitely, wait some more. But no direct solution is offered and they’re not only frustrated by the situation but feel like a bad owner because they have a “problem” dog in the first place and a bad person because they’re considering using an “aversive” after they’ve been lectured on the evils of correcting the dog. In the end, I can give them the ability to live safely and happily with their dog for the duration and without the guilt. Who wouldn’t want that?!

January 21, 2012 at 1:51 pm

Sam Tatters (https://pawsitivelytraining.wordpress.com)

You want a story of a dog being that emotionally and/or mentally scarred that any sort of negative anywhere around him can shut him down, even at the mildest level such as an “uh-huh”?

Welcome to the world of failed sheepdogs, where something as simple as a gentle “no” makes them want to stop attempting behaviours; someone sounding somewhat accusatory to me makes my dog come out in an appeasement rash.

I wouldn’t change it for the world, because I am learning to be a better person, as I help my dog to realise that not everyone will hurt him; and yes, both the farmer *and* broker used at least a choke chain on him, if not a shock collar. Benign they are not.

And in response to Sarah, (“They guiltily tell me that they are a bad person for wanting to “correct” their dog but that they have been doing all positive training for months with no improvement. Or that their dog is great in the classroom but not at home. And when they asked their instructor what to do, they were told to use better treats, wait, be more patient, manage the environment indefinitely, wait some more. But no direct solution is offered.”)

The solution is to to train more, and more often, and be more rewarding than the environment, which means using different treats and toys, as well as managing the environment. Positive training, done well, is the quickest form of learning, especially when paired with a marker such as a clicker. People who only train in class, will only have a dog who is “good” in class because the behaviours have not generalised, which is not the dogs’ fault, but the owners for not taking a little time each day, or every couple of days to train the dog outside of the class environment.

January 21, 2012 at 9:08 pm

ruthcrisler

The existence of such dogs does not argue, in my opinion, against the use of aversives in dog training generally. The exception proves the rule, as they say.

I would suggest that training any dog, including those that elicit considerably less sympathy, has the capacity to make one a better person, as long as one is open to serving the dog’s needs ahead of serving one’s own. In some cases, that means stepping outside one’s personal comfort zone, or using tools and techniques that others frown upon, in order to provide the learning experience the dog needs to succeed.

January 22, 2012 at 7:35 pm

Therese

I have yet to find the treat, toy or alternate behavior that dogs prefer to chasing wildlife or livestock. I do not believe such a thing exists once a dog has developed a taste for the chase. Fortunately, there is good information out there on the proper use of an eCollar to stop chase behavior (one of many things a eCollar can properly be used for). When you have taught the dog the behavior, and you know they understand because they have demonstrated that they do, a well-timed eCollar correction can stop chase behavior and several well-timed corrections can nip the behavior in the bud. I MUCH prefer this to years of “management” that will eventually fail. Solve the problem and get on with enjoying your dog. Patience is definitely a virtue in dog training, but there comes a point where “patience” is merely an excuse for not being able to get the behavior you want with the limited tools you’ve chosen to use.

My biggest model for canine behavior has been my own dogs. They do not pussy foot around in showing what they want of the other dogs in my pack. They maintain such a wonderful dynamic through their huge body-language vocabularies and only occasionally correct each other with the sort of timing and clarity I wish more “trainers” possessed. They do not click or treat each other.

September 4, 2012 at 2:34 pm

metisrebel

Oh amen sister!!! I should ship you an Americano with a side order of butter tarts.

“I MUCH prefer this to years of “management” that will eventually fail. Solve the problem and get on with enjoying your dog.”

My point exactly.

The longer a problem goes on, the more damaged the relationship between the owner and the dog due to frustration and feelings of failure. Period. The longer a bad behaviour is entrenched, the more work to root it out.

If a quick correction or an e-collar solves the problem it is a momentary discomfort between them and they can get on with living “happily ever after”.

January 23, 2012 at 9:32 am

Sarah

“Positive training, done well, is the quickest form of learning, especially when paired with a marker such as a clicker.”

Sure, I’ll give you that. I just read a book that discussed the process of shaping using positive reinforcement. Two basic requirements for teaching behavior with +R & shaping was to have lots of time, potentially set aside an hour or more on the first session, and select a specific environment that you’re in control of. But learning a new behavior has to eventually become PROOFING said behavior to ensure the behavior is generalized and reliable (unless of course the dog is not permitted to leave the training environment), and in my experience, that’s where most people jump the +R ship because they quite intelligently recognize the limitation of having one hand tied behind their back. The fastest way to realize reliability and proof behavior is to incorporate some amount of punishment into the equation, to ultimately respect a dog enough to recognize that he can make a decision about his response and behavior; he’s not simply an organism to be conditioned, but a thinking and calculating, sometimes impulsive, and instinct-driven being.

Sam, I’m not sure if you’re a trainer or an enthusiast. I often find that the most vehement opponents of any sort of balance in a training approach haven’t had the opportunity to deal with a wide range of behavior problems, breeds, and temperaments and it often boils down to a situation where they’re speaking from their experience working with a few relatively biddable dogs. I’m not asking you to change what you do. But please don’t delude yourself into thinking that the admonishment to “…train more, and more often, and be more rewarding than the environment, which means using different treats and toys, as well as managing the environment,” washes with everyone.

That’s one of the pitfalls of pushing a religion over results. Unlike true religion, in dog training, “seeing is believing” is a legitimate concern for one who’s paying for a service. If they don’t ultimately see the results they expect, they stop believing in the righteousness of the approach and they don’t care to try harder at that point because they’ve lost faith. I don’t sell an ideology. I don’t have to describe how humane training is, I can show them results and they can see their dog is not traumatized and is better-behaved for it. I choose to be a trainer that can provide a solution for these people instead of more of the same excuses, blame-shifting, and moral crusading that’s been previously foisted upon them.

January 23, 2012 at 10:43 am

ruthcrisler

Sarah, very well said. Thanks so much for your comments.

January 23, 2012 at 4:10 pm

Linda Kaim

Particularly fond of this:

“I choose to be a trainer that can provide a solution for these people instead of more of the same excuses, blame-shifting, and moral crusading that’s been previously foisted upon them.”

Perfect in it’s understatement.

September 25, 2012 at 12:56 pm

Jessica

And eventually what happens when these people who have problematic (read: aggressive) dogs go from trainer to trainer in their area and are turned down or put off over and over again, is that the dog’s behavior escalates in severity and the dog is killed.

My school has been the last chance of many a dog, and we have had clients who would not use careful corrections on their dogs and left over this philisophical point, a year or two later have called back to let us know that the dog is now dead after sending a person to the hospital. And this is after working with aversive free behaviorists and trainers.

January 21, 2012 at 2:35 pm

shepherdpal

Awesome post and right in line with what my trainers says

January 21, 2012 at 3:03 pm

Robin MacFarlane

Brilliant. Thank you Ruth. There are so many comments I could make on this post due to the wealth of opportunities you have provided me with “yes!” moments as I read and re-read it.

But I will point out this one in particular as I found it so stunningly relevant: “It is a lesson in training one’s inner voice to distrust one’s rational mind.”

…and this, this is exactly the “training” that is going on in far too much of the dog community today. Handed down from the preachers, to their disciples to spread to the community at large with little actual thought being given as to what really makes sense.

Fortunately, simple questions posed to those clients who seek us out after multiple failures with the “all positive” agenda like “What do you think?” and “How did your dog respond?” begin to lift them from the daze. I’ve seen the light flicker many times as the realization hits that perhaps the holier than thou anointed ones where actually practicing a bit of voodoo.

January 21, 2012 at 4:01 pm

Victoria

I love this article. I can’t wait to dig around in this blog some more. I am facinated by people’s need to break down trainers and training into all positive or devil take the hindmost. Nothing is ever going to be that simple! All of it must be teased apart and examined- for each and every dog. We are all situational learners and ethics evolve. And I surely agree that to equate aversive with abuse is to not understand the pathology of abuse. I have more to say- but I’d rather indulge in some fun reading on this site.

January 21, 2012 at 6:04 pm

Viatecio

Sarah said “And while I am by no means the perfect trainer and still have much to learn (and am actively seeking to learn it), almost every one of my clients has done some form of “all positive” training before working with me.”

While no offense is meant toward trainers who prefer to not use aversives, I do agree with this.

If the “Trained dogs” coming out of the local clicker-trainer’s class are anything toward which to strive, I quit the business here and now.

September 4, 2012 at 2:38 pm

metisrebel

I’ve noticed that at the park.

Not ONE “average owner” with a food/clicker dog can let their dog off lead [that was out of counting 100].

Most of them barked, acted out and carried on while I spoke with the owners.

I don’t CARE how many “tricks” they do–most of them are butt-awful when it comes to simply laying down quietly while their owner talks in the presence of another dog.

January 21, 2012 at 6:39 pm

Summer Milroy

Great article. Thank for posting this Ruth

January 21, 2012 at 7:12 pm

Angela Bentley

Very well written. Looking forward to more…

January 23, 2012 at 12:15 am

The Lessons On Mountain’s Muzzle | Pet News

[…] All of this is a wind-up to a truly excellent piece from Ruth Crisler about real world aversives and the fomented fear and contrived crisis fanned by certain dog trainers who seek to browbeat the world into thinking there is only one way to train a dog. Read the whole thing. […]

January 23, 2012 at 3:06 pm

Diane Garrod

The heavy hand myth – you don’t need fear or pain to train (teach) dogs. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WGZnQlFevf0&feature=youtu.be

My answer to your original question would be neither one – that is the “rational” answer, the knowledgeable answer. It is good to read your views but there are a lot of misinformed content here. Positive is not permissive; but it is educational.

Oh..did I mention I work with aggression daily AND take multi-dog fighting cases in the home, that others won’t take. Positive simply last longer. Respect is initiated and then the dog respects the process and you or their owner. If you really used positive training to get results, and in the right way. I believe those myths about treats and all that other misinformation that gets tossed out is why these articles are written. Here is another really good piece, and by a man. These videos you will view have “real men” in them. Go figure.

Three of the most common dog myths “debunked”:

Dog Myth Nr. 1: Clicker Trained Dogs Only “Work” for Treats

Dog Myth Nr. 2 .. Harnesses encourage pulling

Dog Myth Nr. 3: When your dog walks in front of you, she’s exerting her dominance

This is not a woman’s game, this is that dogs respond to positive handling. Men get this too.

January 23, 2012 at 5:18 pm

ruthcrisler

Diane, you are attributing a number of beliefs to me that I do not hold, much less actively promote. Just sayin’.

As for the “women” comment, I suppose I should have assumed that would be misinterpreted, but anyhow, I’ll attempt to clarify. I am not suggesting anything so broad as that the positive reinforcement movement is either driven by or practiced chiefly by women. It may be, but that’s neither here not there. I was observing that the sort of moralizing cited in my blog post seems mainly to be voiced by women. And as a woman myself, I find that vaguely disturbing.

Incidentally, I spent a very productive hour this morning working with a highly reactive dog and his owner. The tools involved? A Halti, a leash, a known trigger, and a boat load of treats. It was a rewarding session for everyone involved.

I’m not against positive reinforcement. I’m against narrow-minded, sanctimonious rhetoric geared toward creating strict (and in many cases, counter-productive) ideological constraints on dog trainers.

January 24, 2012 at 4:29 pm

Rick

Diane,

“You have to punish in training…..you have to let the dog know ‘that’s right’, and then you have to let the dog know ‘no, I don’t want that type of behavior’. Punishment should be punishing…..”

—-Ian Dunbar (from the video in your link above, beginning @1:00)

January 23, 2012 at 9:24 pm

Ada Simms

It seems apparent the treatment of an animal should have no boundaries or the tools used to obtain “obedience” from tje dog.

The statement “I’m against narrow-minded, sanctimonious rhetoric geared toward creating strict (and in many cases, counter-productive) ideological constraints on dog trainers”.

I have heard this statement, not verbatim, but similar statements when laws were made to prohibit child abuse..or let me say hitting a child by hand, or belt, paddle, cigarette burns, hot water. Parents were outraged that they should be told by narrow minded psychologists and psychiatrists, let alone the gov’t creating strict ideological restraints on how parents manage their own children. How dare anyone restrict the right of a parent.

Not only that, but now spouses or significant others can’t control their partners through force, fear, intimidation, no more slapping…how ludicrous.

But dogs…well they are just considered property, so why would there be rules to govern their humane treatment. Really they are only dogs.

So just for giggles in the paragraph that Ruth just stated, instead of constraint of “dog trainers” substitute some of these words… parent, spouse, or slave owner, even pimp. If you find it distasteful or upsetting then you are a compassionate person. If you don’t see the analogy, then dogs are just objects to obey your every whim in any manner you chose.

January 23, 2012 at 9:53 pm

ruthcrisler

Thank you for reinforcing a central point of my blog post, namely that the current arguments against punishment in dog training tend to rely heavily on emotionally charged rhetoric and ugly innuendo.

January 23, 2012 at 10:17 pm

Ada Simms

And thank you for your response. Your stance is clear. I expected the robotic floral answer without emotion or compassion for other living things besides humans. Your point is made quite clear.

January 23, 2012 at 10:23 pm

ruthcrisler

You’re welcome.

January 24, 2012 at 6:04 am

Viatecio

How does child abuse relate to the appropriate, humane and effective use of aversives, whether used purposefully in dog training or encountered by accident in daily life of either dog or child?

If “dogs are just objects,” then what are whales to trainers and park owners? Waterproof cash?

Even moreso when something happens to remind everyone that the only “relationship” that exists between said cash and the trainers is that based on starvation and environmental/social deprivation?

Yet, behold the poster child of the anti-aversive crowd (I refuse to say “Positive-reinforcement” crowd, since every good trainers uses R+)!

January 24, 2012 at 12:46 pm

Viatecio

As an aside, I have heard the “compassion for other living things besides humans” line before too and wondered when it would come up in conversation here.

How is the appropriate redirection of attention through the use of a startle technique (that which is here termed “aversive”) “condemning another living creature” or showing a lack of “compassion for other living things besides humans”? The dogs with whom I’ve worked would most likely be puzzled by your words, as they are living happily with their families receiving praise for doing things the right way, which was taught with such “condemnation.” Their lives are much improved, their relationships with their owners are the best they’ve ever been.

If this is “without compassion for other living things besides humans,” then by all means, string me up on animal cruelty charges. Obviously I am doing something wrong by bettering the lives of these dogs and their owners without resorting to blind ideology, laughable “science” (indeed, more abusive than laughable in some cases as Ruth notes in earlier blog entries), and excuses such as what I read above (“train more, and more often, and be more rewarding than the environment” etc etc) when the dog that is more than capable of learning is NOT learning, even very basic concepts, within what I consider a reasonable time frame (AKA not weeks or months).

Forgive me for not seeing your analogy, Ada. After all, your words (“dogs are just objects to obey your every whim in any manner you chose”) sound very much like those often used by activists who are against the inclusion of animals in our society at all–even for companionship, much less purposes that actually aid us in any way, shape or form. I do not subscribe to such thinking, and as even basic obedience should constitute steady focus and reliable, one-command performance that might appear to some as “obey[ing] every whim”…it’s no wonder the standards for obedience training have declined over the years.

After all, a dog that runs to greet others, jumps on people, etc is “happy” and “sociable.” If it responds the second or third time its owner commands it or whenever the reward comes out (regardless of what that reward is–not always food) it’s a “trained dog.” However, if it responds the first time, immediately and without question, regardless of the distraction, it’s “obeying its owners every whim in any manner” or even a “robot.”

Don’t get me wrong, I’m all for positive reinforcement. If someone can get a dog to that one-command, immediate response in the face of distractions (and off-leash is a plus) using no aversives, that’s fine. I say go for it. We’re all in the business of helping people and dogs. I’m not against that.

Just don’t have a cow when others can do it too, even if it’s with tools and techniques with which you disagree, within a shorter time frame, and without resorting to excuses or treating the owners like they don’t deserve to have the whole picture when it comes to training and behavioral modification because they’ll irreversibly mess up their dogs if they apply anything more aversive than a shaker can or a squirt bottle.

Because after all, if we’re ALL in the business to help dogs and do it humanely and effectively, but SOME (and who is doing the labeling is just as important as the ones being labeled!) have no “compassion for other living things”…what happens when clients start choosing trainers based on results instead of ideology and theory–as Sarah has mentioned with some of her clients–and discover that “compassion” includes embracing the whole of learning theory instead of the parts that feel/sound good, all while avoiding the extremes of abuse?

January 24, 2012 at 9:47 am

Linda Kaim

Viatecio writes:

“Yet, behold the poster child of the anti-aversive crowd (I refuse to say “Positive-reinforcement” crowd, since every good trainers uses R+)!”

Setting aside the fact that what they wish to extend to animals, they refuse to impart to their own kind with this self-masturbatory rhetoric, forgetting that marine mammals don’t resource guard the couch, chase the kids in a predatory manner, raid the trash or eat the cat.

They just kill their handlers, after years of deprivation in a fish bowl, their survival diminished by half of their natural life-span, paraded as the font of +R plus virtue.

Spare me.

January 24, 2012 at 3:52 pm

ljcdogsLeonard Cecil

The last I checked, I’m still a man – in fact the guy in the three linked films above. The dog shown is mine and is dog-dog as well as dog-human reactive, albeit not of the aggressive sort. Plus she is super soft, a harsh word will set her groveling, alternating trying to get away and licking feet appeasingly. The dog has never been positively punished since having made that deduction.

You might say, “Sure, one super soft dog and a biddable retriever to boot.” but in the meantime I have a small practice dealing with mostly aggressive dogs. Working with the owners, keeping dogs entirely under threshold, all of them no longer depend upon aggressive displays to protect themselves against people. I don’t insist upon clickers, although some clients do use them to great advantage. I do however insist upon relationship & trust building which cannot be done using aversives and besides that, simply is not necessary, since the dogs are learning several things:

1) to communicate their need for distance to the object of their previous aggression to their human

2) that their human will understand this and respect this need

3) that their human will not put them in an for them untenable position, simply for the sake of convenience (like getting quickly from point a->b

But other things are happening at the same time.

1) the human is learning that dogs do have a legitimate point of view. they have fears, likes dislikes

2) a human-dog partnership doesn’t have to be one way, with the human saying “my way or the highway”. Understanding this is like teaching a child the meaning of the term “not yet”. A dog can learn this too – ie “impulse control”

3) the dogs, through NOT being forced via compulsion to face the object of it’s previous aggression on terms which are out of his control, learns that this previous object of aggression is NOT so bad after all. this is the classical conditioning that compliments the operant conditioning from above.

The key to the whole puzzle is having the human think about what kind of relationship he/she wants with the dog. There’s a reason I can work with a dog that accepts me, even if it takes 5 weeks for the dog to do so, and have a velcro dog, while that same dog regularly blows off the owner. It’s because I have no aversive history with the dog. The dog has no reason, once the relationship has been established, to believe I will ever do anything “bad” to her. Because I never have. Doesn’t mean I’m permissive. I can be a tough cookie (sorry the pun) when wanting something done and done properly, but I have no need to lay a hand on the dog or use an aversive tool. I often simply drop the leash and let it trail. The dog learns that co-operation is more in his own best interest than anything else. the leash stops being a source of connection to an aversive. And the dog is behaving like any other biological being – acting in her own best interest. And it’s that best interest that also melds into the human’s own best interest – having a harmonius, relationship based upon mutual trust and mutual co-operation instead of avoidance (fear) of pain.

But the human has to set the goals, I can only lay them out for him. and some people just want a dog that obeys.

so now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to get another beer, finish watching the game and scratch some unmentionables. Very un-lady-like of me, I know, but there you have it.

January 24, 2012 at 7:48 pm

ruthcrisler

I have no issue with your training methods or philosophy (or gender). And I respect the tone of your comment.

I am not a heavy-handed trainer. I am an open-minded trainer. And I am an honest one. When I use aversives, I do so purposefully and unapologetically. I do not stick head halters and anti-pull harnesses on dogs and claim to be taking a “positive” approach. I do not demonize prong or electronic collars for being aversive, while reveling in how effectively my Gentle Leader or Gentle Spray deters unwanted pulling or barking. And I’m not saying you do, by the way.

Nor am I saying that everyone MUST train with aversives. But I don’t really buy that one can remove them entirely either. Restraint and confinement are aversive. Withholding food prior to training is aversive. If these are elements of one’s training/management program, it’s not all-positive in my book.

For every dog and training challenge, there is some set of optimal solutions. Even supposing that it was realistic to train 100% aversive-free, that would not likely represent the optimal solution for most dogs, much less EVERY dog.

The question is, how do we measure things like cost to the dog (e.g. stress, discomfort, boredom, confusion, isolation), versus gains to the dog (e.g. confidence, success in the home/in public, rewards/privileges, practical skills, mental/physical exercise), if we are not able to discuss tools and methods openly and objectively. We cannot compare the cost and/or effectiveness of two tools intelligently, if one is arbitrarily labeled “abusive” and the other “gentle”, despite the fact they each cause varying degrees of discomfort depending on how they are used. Nor is it helpful to casually compare trainers who use aversives unapologetically to child abusers, while heralding trainers who use aversives guiltily or grudgingly as positive and humane.

Equating aversive with painful, or equating punishment with abuse, is beyond intellectually sloppy. It is deliberately dishonest.

That’s what I have a problem with, not the fact that every dog on the planet isn’t wearing a prong collar.

January 24, 2012 at 11:51 pm

ljcdogsLeonard Cecil

“Equating aversive with painful, or equating punishment with abuse, is beyond intellectually sloppy. It is deliberately dishonest”

Sorry, but YOU are doing that. Punishment is a necessary part of learning, but as Ian Dunbar says, (paraphrasing, since I don’t have the exact quote in front of me) -if punishment doesn’t have to be painful or fear inducing, then there is no reason it needs to be.

With all the myriad ways of training virtually ANY kind of dog activity and handling virtually any kind of behavioral problem without using pain or fear inducing methods or tools, then why would one CHOOSE to use them?

And just as there is a myriad of way to train using positive reinforcement/negative punishment and extinction (negative reinforcement being the absolute exception), there is a myriad of REASONS why one would choose to use pain, fear and/or intimidation.

And to this end, two quotes come to mind:

“Violence begins where knowledge ends.” -Abraham Lincoln

“In dog training, ‘ jerk’ is a noun, not a verb.” -Dr. Dennis Fetko.

January 25, 2012 at 12:16 am

ruthcrisler

I am beginning to think you did not read my piece very carefully. I am in no way, shape, or form equating these things. Nor have I made the slightest argument for “fear and/or intimidation.”

Not even close.

January 25, 2012 at 3:30 am

ljcdogsLeonard Cecil

No, no I read your article and very carefully. It’s very well thought out and crafted, as Jean Donaldson would say “weasel oil”. It is an attempt to skitter around the basic ethical and moral questions posed by the applications of that, which the animal perceives to be aversive, not what we perceive to be aversive.

First come the individual moral and ethical borders one sets up oneself

Then come the investigations as to which methods can be used within those moral boundaries.

That’s leaving the science completely out of it, but we can talk about that too.

Once you have made the moral and ethical decision that human induced dog perceived aversives as consequences of their behavior are legitimate, then no other justification is necessary except perhaps how far you are willing to go. This is quite clearly stated by Michael Ellis who claims that giving a soft Golden Retriever a good jolt from the e-collar is (in his opinion – note LC) more human than risking training frustration using negative punishment. Here is a well thought out personal line in the sand drawn by someone who will not come within 50 yards of my dog. But he’s done the soul searching, put it out there and stands by it. that the science doesn’t support him in terms of effectiveness of mixing aversive consequences with positive consequence is at that point, of no real importance.

My only point in replying here, since I’m pretty sure you’ll agree, none of us are going to change the mind of the other is, to strip away some of inaccuracies and incorrect pretenses. While of course stating a slice of my own POV. What’s “right”? Your own ethical and moral standards, what you find allowable in interacting with people or animals. In end effect, no more, no less.

January 25, 2012 at 6:17 am

Viatecio

“Equating aversive with painful, or equating punishment with abuse, is beyond intellectually sloppy. It is deliberately dishonest.”

Leonard, I believe you were reading Ada Simms’ words in regards to child abuse (on how children used to be punished back in the day), on which I expounded in my above comments.

The only ones here who are equating fair aversives that the dog ackowledges in training, such as leash corrections, to abuse are those who feel that it is the case.

These are the same people who have no issue with applying a squirt bottle or shaker can to the dog as a form of an aversive. And these do work to some extent in many situations with a lot of dogs. The issue comes when these things fail, whether because of the situation or because they simply are not perceived as an aversive by the dog.

And that is when trainers who are open to other forms of aversives without resorting to abuse have the option of applying them, IF they are in the dog’s best interest and help the situation; or not applying them, if they feel there are other ways around the issue.

Obviously, the choice is up to the individual trainer–as long as the dog benefits and learns.

Are you aware of the conviction of a Loveland, CO dog trainer? He chose to abuse his dog. This is not training, no matter how you spin it–it is not “misuse of punishment” and to use this story as so many others do to villify good trainers who do use aversives as necessary in an otherwise positive-reinforcement-based program is wrong–I’d say that those people KNOW it’s wrong, but when the zeal is such that No Other Way But Theirs is “correct”…well, then there really is no solution.

By the way, that Abe Lincoln quote…cool, but I don’t think he was referring to dog training. Unless he was being prophetic about Ryan Matthews and the rest of the ilk that still think beating dogs is the way to go. Remember, they also had bigger fish to fry back in those days, like that pesky Civil War thing and the issue of slavery, treatment of black-skinned peoples, etc…

January 25, 2012 at 7:11 am

ljcdogsLeonard Cecil

No, the quote was taken directly from Ms. Crisler’s posting.

January 25, 2012 at 9:10 am

ruthcrisler

Interesting you should bring up Jean Donaldson, since she uses aversives and compulsion herself, although less skillfully than many of the trainers she vilifies.

Here is Donaldson forcing a reactive dog to sit facing another dog through the rather awkward application of negative reinforcement. For the record, I find this protocol very unfair, and it is approximately the last technique for handling a leash aggressive dog that I would publicly recommend. But hey, I guess if you’re humane and positive enough, you get to use force and aversives with impunity, even while railing against trainers who use them more carefully and responsibly.

http://abrionline.org/player.php?id=102&height=440&width=700

If that link doesn’t work, visit http://abrionline.org/search.php and search for “Tips for Handling a Dog-Reactive Dog”. This technique is described beside the video as “painless negative reinforcement”, by the way. You may also want to check out Donaldson’s “Working with on-leash Aggression” video, in which she man-handles a leash aggressive dog with a Gentle Leader in a manner described as “fluid”.

My point is not that Gentle Leaders are evil, or that Jean Donaldson is evil, or that negative reinforcement is evil. It is that there is an awful lot of hypocrisy in dog training today. The fact that Jean Donaldson simultaneously recommends the use of negative reinforcement (which relies by definition on the application of an aversive), advertises her methods as “aversive-free”, and attacks trainers she dislikes for using aversives themselves, is just one example.

January 28, 2012 at 11:17 pm

Rick

And speaking of hypocrites, here is Victoria Stilwell using and ecollar to deliver an aversive to a dog. Personally, I would rather be shocked a thousand times at my dog’s working level than have that dominatrix barking in my ear. Talk about inhumane!

January 29, 2012 at 9:28 am

Rick

Oops! Here’s the link

January 29, 2012 at 9:48 am

ruthcrisler

Ah, yes. I remember it now. It’s remarkable how clumsily she applies the aversive. Hopefully she’s gone back to berating humans exclusively, an activity she obviously finds highly reinforcing.

January 25, 2012 at 6:43 am

Paul McNamara - Certified Average Pet Owner

On the question of ethics. I think that any effective method of dog training will necessarily (insofar as it is effective) bring about a happy, confident, well mannered, reliable dog. And insofar as the trainer is effective in bringing about such results, the ethics take care of themselves.

Whereas when the issue of ethics arises in regards to tools and methods, independently of the results, it almost always signals a crisis that properly seen is not ethical, but practical.

When the practice is right – meaning, when it brings about a happy, confident, well mannered, reliable dog – the question of ethics does not arise.

January 25, 2012 at 7:09 am

ljcdogsLeonard Cecil

“On the question of ethics. I think that any effective method of dog training will necessarily (insofar as it is effective) bring about a happy, confident, well mannered, reliable dog. And insofar as the trainer is effective in bringing about such results, the ethics take care of themselves.”

What I said – if you find using choke collars, prong collars, chemical sprays e-collars, e-fences, all of which operate by causing the dog pain and instilling in the dog fear of the pain being repeated (avoidance conditioning) to me ethically and morally ok, then you have made your choice, just as I have to NOPT use these things. It’s all a matter of ethics and morals.

January 25, 2012 at 7:36 am

Paul McNamara - Certified Average Pet Owner

If such things as choke collars, prong collars, ecollars etc, instilled in “the dog fear of pain being repeated” then it follows logically that one’s methods have NOT produced ” a happy, confident, well mannered reliable dog”.

Your response is but an example of “training one’s inner voice to distrust one’s rational mind”.”

January 25, 2012 at 8:59 am

ljcdogsLeonard Cecil

Are you claiming, that choke collars, prong collars, chemical sprays and shock do not cause pain? A dog doesn’t go around all day wondering when the next shock will come. But put the dog in the proper context, for example on a field where she has received multiple shocks and you will see a different dog than in other contexts. so it’s very possible, that a dog can be happy until she sees the trigger that signals a context in which she has received physical punishment.

Just today at the street-car stop. I’d gotten off the bus after having met a super-sweet Akita. They left the bus by the front door and I the back. Went onto the stop to wait for the street car. A gentleman came by with his 13 year old Irish Setter. The Akita started rumbling. As soon as that started, the verbal reprimands started, the Irish Setter came closer and the leash was tightened, at which point the Akita started barking. The came the tugging against the straining, barking Akita. Obviously

1) the owners had been through this before and had done the same thing. Repeating failed tactics, hoping they would work -this time- I b elieve einstein had a nice saying about that

2) as the owners punitive measures increased, so increased the dog’s reaction towards the other dog. The dog had learned, that the closer the other dog came, the more violent the reactions of the owner towards him would become. Since the dog had not experienced anything else, was not taught to behave differently, the dog had no other option.

3) and it worked – the owner of the Irish Setter saw a barking lunging Akita, and listened to his dog’s frantic calming signals directed towards the Akita, and turned around and went away. The Akita was once again taught that approaching dog means reprimands moving over to leash tugs and jerks from owner, so better get that other dog out of here.

Punitive measures did not help, but rather provoked the behavior. Was the dog happy? on the bus while he was licking me and I was scratching his chest, sure. During the encounter with the Irish Setter, certainly not. It would have taken maybe 2-3 sessions to teach that Akita how to behave differently using positive reinforcement, but most people here would rather hook up the choke, prong or e-collar to -suppress- the behavior. Suppression is completely different than behavior modification. In behavior modification you can teach the dog to yearn for that approaching other dog instead of trying to scare it away. Suppression just forces the dog to hide the basic emotion involved, but has to be applied in every single instance.

The ethics and morals come into play in terms of what you want. Do you want a co-operative dog or just an obedient dog. You can get an obeident dog without the dog’s co-operation, but suppressing all forms of unwanted behavior. We’ve all seen the dog lapping along next to the owner, not sniffing, looking left or right, or even at the owner. 9 times out of 10 you can be sure that dog has been punished until the dog is afraid to do anything on that leash. Granted, an extreme case.

OTOH, watch this film especially the part with the behavior chain. The dog makes a “mistake” and without cue from me, rectifies it. A dog trained with punishment will understand that she’d made a mistake, but then not dare to move or solve the problem herself – will be very uncertain and hesitant to do anything and wait for instructions or (gasp) the expected punishment.

January 25, 2012 at 9:48 am

Paul McNamara - Certified Average Pet Owner

“Are you claiming, that choke collars, prong collars, chemical sprays and shock do not cause pain?”

No, I am not. I have made no argument in relation to which tools a trainer does or doesn’t use.

“A dog doesn’t go around all day wondering when the next shock will come. But put the dog in the proper context, for example on a field where she has received multiple shocks and you will see a different dog than in other contexts. so it’s very possible, that a dog can be happy until she sees the trigger that signals a context in which she has received physical punishment.”

You are describing a situation in which the method/tools that have been used have NOT produced a happy, confident dog. In such a situation it is very much the ethical duty of the handler to reconsider his/her methods.

“Punitive measures did not help, but rather provoked the behavior.” Again, you are describing a situation in which the methods/tools applied have NOT worked to produce a happy, confident dog. The owner of the Akita, does indeed IMO have an obligation to reconsider his methods.

“It would have taken maybe 2-3 sessions to teach that Akita how to behave differently using positive reinforcement, but most people here would rather hook up the choke, prong or e-collar to -suppress- the behavior.”

I am not a dog trainer, just an average pet owner, yet even I know that your statement as to what “most” people here would do is both ignorant and false. And the falseness of your statement has nothing to do with the tools in question.

“The ethics and morals come into play in terms of what you want. Do you want a co-operative dog or just an obedient dog.”

I have already told you what I want and expect: a happy, confident, well mannered reliable dog.

January 25, 2012 at 11:29 am

Rick

LC said: “But put the dog in the proper context, for example on a field where she has received multiple shocks and you will see a different dog than in other contexts. so it’s very possible, that a dog can be happy until she sees the trigger that signals a context in which she has received physical punishment.”

But it’s also very possible that the dog will continue to be very happy on the field or wherever, as so many of us who’ve used ecollars correctly have observed. That sort of argument may play well among people who have no experience with proper ecollar use, but those of us who have first hand experience with ecollars, and have happy, confident, well mannered, reliable dogs, aren’t persuaded.

July 11, 2014 at 3:21 pm

Amanda

What happened with the Akita doesn’t sound like the dog has been trained at all, just a dog owner making a guess at what to do, ignoring that it doesn’t work, and not wanting to condone the bad behavior by doing nothing.

And I contest that a dog who has been trained with aversives don’t self-correct – I’ve seen them do it all the time. Most frequently in the case of coming to a halt while heeling, they’ve halted too far ahead, and then back up to proper heel position before I can let them know they’ve sat too far ahead – or a dog starts to break from a stay, even so far as standing up, but then sits back down. At a trial my dog came in too fast for her recall to do a straight sit in front, she blew past my left side and turned around and sat in perfect heel position. Many, many instances of dogs trained with aversives self-correcting.

January 25, 2012 at 7:17 pm

If dogs think and feel, do aversive training techniques cause harm? « Heavenly Creatures

[…] K Schrute, “The Office”*Oh boy. Dog trainers are butting heads again over a post on Ruth Crisler’s blog, called “Undo Temperance.” Butting heads figuratively, of course. Because we don’t want to ever butt heads literally. […]

January 26, 2012 at 6:44 am

Cindy Ludwig

Very eloquent and interesting writing, Ruth, but as professional educator and Karen Pryor “disciple,” someone whose training has evolved from compulsion to lure reward training to clicker training, I have to disagree that aversives are necessary or justifiable in dog training.

It’s not about “religion,” it’s about relationship – the relationship I choose to have with the animal I am training. For me, not using known aversives in animal training is not even so much about ethics as it is about effectiveness. I would rather develop a thinking animal than a passively obedient animal. I would rather have a relationship with two-way communication than a dog that passively submits.

Are head halters aversive? Yes, I believe they are, so I agree with you that intent has not got a lot to do with whether something is aversive or not. Am I a hypocrite? Perhaps, because occasionally I use them – but, I also take my time to desensitize, countercondition, properly fit the collar and teach the owner how to properly use the collar. I also screen owners carefully these days before recommending a head collar.

Pain, whether psychological or physical is a very individual and subjective vital sign. It is impossible to measure objectively but we can observe for signs that indicate discomfort, signs of stress – a barometer of sorts of receptiveness to learning. And that is precisely what clicker trainers do. We observe the animals we are working with very closely for their response to our training and we adjust accordingly to keep the animal working at an optimal level – challenged, but not frustrated.

Is it possible to totally avoid aversives in training? Well, arguably it may not be. For example, one time when I was at a weekend workshop in the Karen Pryor Academy I was attempting to use some commercially prepared treats with my dog, Ginger and as I handed her the treat, she turned her head away! She found them aversive!

I do not believe for a second that training without aversives sacrifices results; rather, results achieved through cooperation rather than compulsion are results that are not only reliable but resistant to extinction.

And while it is interesting to ponder whether it is possible to effectively apply positive reinforcement training in a less than controlled real world setting, the fact is, we apply theoretical knowledge every day in other fields of applied science – and get results.

As a professional nurse with many years experience I could also give you examples of how we as medical professionals who are after all, only human apply best practices to the care and treatment of our patients and yet, despite our best efforts confounding variables that are beyond our control cause “complications.” Does that mean we stop trying to apply best practices – best practices based on scientific evidence?

Nope. We regroup, re-evaluate and carry on with the pledge to “first do no harm.”

January 26, 2012 at 6:46 pm

ruthcrisler

Cindy, thank you for your very thoughtful comment.

I agree with your statements regarding the importance of adjusting one’s approach at every step according to the signals the dog displays. Such business will never be wholly free of subjectivity, of course, but it still comprises the most essential “feedback loop” available to any trainer. And the ability to read a dog properly is an essential skill for any trainer, as well. But I don’t believe it’s a skill that distinguishes clicker trainers, or “positive reinforcement” trainers, from trainers who are more comfortable with applying aversives responsibly. Ignoring or misinterpreting a dog’s signals, or denying their relevance, is simply the mark of a poor trainer.